Reduce interruptions to help engineers stay in flow

Interruptions — anything that yanks a developer out of that elusive “flow” state — can appear out of nowhere. They’re often untracked and underestimated in their ability to derail focus and productivity.

Some interruptions are truly urgent and require immediate attention. Others stem from outdated processes or habits and can be scheduled for later. An approach based on the Eisenhower matrix can involve categorizing interruptions based on urgency and impact and then devising a strategy to handle each category effectively.

- Urgent and important. Issues like production outages that demand immediate attention and generally have team-wide consensus for prioritization. Certain customer situations can also fall into this category.

- Important but not urgent. These include helping a colleague with a code review or discussing a new feature in a meeting. Important, but not time-sensitive.

- Urgent but unimportant. This is the class of interruptions that could be solved by an engineer, but an equally good and more timely response is available elsewhere.

- Neither urgent nor important. Questions or issues that could have waited or been solved through other means. These are especially disruptive because they often don’t warrant the break in focus they cause.

This post dives into systemic interruptions requiring a broader organizational fix rather than individual adjustments: interruptions like meetings, internal support, external support, and production incidents. These interruptions not only impact the effectiveness of individual software developers but can also destabilize teams and processes as a whole, especially as a company scales.

For the sake of this post, we’ll define an “interruption” as anything that yanks a developer out of that elusive “flow” state. Getting back into flow can easily cost a developer anywhere from 20 minutes to an hour or more. In this scenario, a task that might have taken a single day can easily expand into multiple days. If you planned for this unpredictability, you’ll be fine; if not, interruptions can disrupt your delivery and roadmap.

The meeting quagmire

Meetings within an organization exhibit a wide range of effectiveness — while some prove to be instrumental in decision-making and collaboration, others can be, well, nearly worthless. The underlying cost of a meeting isn’t limited to its duration; it extends to the interruption of deep focus, which is vital for productivity in roles like software development.

Engineers should be encouraged to designate blocks of time for focused work, and these should remain inviolate. Features like auto-decline can safeguard these precious hours, preserving dedicated work time.

The frequency of meetings often correlates with job responsibilities. Leadership roles, such as engineering managers and tech leads, may find their schedules more populated with meetings than their junior counterparts. Despite this variance, a universal objective should be to secure uninterrupted blocks of concentration, aiming for X hours of focused work Y days a week, ensuring efficiency remains at its peak.

For example, you might consider an engineer to have “sufficient focus time” if they have at least four uninterrupted hours each of at least four days a week.

Minimizing meetings can free up significant blocks of productive time for teams. Here are some effective strategies to consider:

- Clear objectives. Before scheduling a meeting, clarify its purpose. If the objective can be achieved through an email or a quick chat, opt for that instead.

- Audit recurring meetings. Periodically review standing meetings to determine if they’re still relevant or if their frequency can be reduced. Some weekly meetings might be just as effective if held bi-weekly or monthly.

- Agenda requirement. Insist on an agenda for every meeting. This not only ensures that the meeting stays on track but can also help participants evaluate if their attendance is essential.

- Time limits. Set strict start and end times. Use tools that default to shorter meeting lengths (like 25 or 50 minutes instead of 30 or 60) to encourage efficiency.

- Limit attendees. Invite only those who are essential to the meeting’s objective. A smaller, more relevant group can often make decisions more quickly.

- Decision-making protocols. Establish clear protocols for decision-making that don’t always rely on group consensus. Empower individuals or smaller teams to make decisions where appropriate.

- Asynchronous updates. For meetings that are informational or offer updates, consider asynchronous methods. This could be in the form of recorded video updates or written reports that team members can review on their own time.

Internal support

Internal support in a software organization can be envisioned as the backbone that ensures the smooth functioning of teams, particularly as software engineers assist their peers in navigating and completing tasks. It acts as a bridge, filling in knowledge gaps, clarifying doubts, and facilitating better understanding. Yet, as vital as it is, this very support system can become a significant source of interruptions, especially when the demand surpasses the supply of knowledgeable peers who can assist.

One major contributor to the increasing demand for internal support is the absence of self-serve solutions. In an ideal scenario, engineers would have tools or platforms at their disposal where they can independently find answers to their queries. Without these, they’re left with no choice but to seek out help from others, leading to frequent interruptions for both the one seeking help and the one providing it. Similarly, when “happy paths” or clear, straightforward processes for common tasks aren’t established, engineers often find themselves in the labyrinth of trial and error, pulling in colleagues to help navigate.

Further complicating the situation is the lack of comprehensive documentation. Documentation acts as a roadmap, guiding engineers through processes, tools, and solutions. Without it, even routine tasks can turn into lengthy, interruption-laden challenges. Perhaps more insidious is the issue of knowledge siloing. When knowledge becomes the domain of a select few and isn’t disseminated broadly, it creates an environment where constant queries become the norm. Those in the know are frequently interrupted, and those out of the loop are continually seeking guidance.

In essence, while internal support is an invaluable aspect of collaborative work in software organizations, without the right structures and resources in place, it can morph from a support system into a persistent source of disruptions. Properly addressing the factors that increase the demand for internal support can mitigate these interruptions, leading to a more efficient and harmonious work environment.

Internal support, while essential for collaborative efforts within a software organization, can place several burdens on individual engineers:

- Time drain. The most immediate impact of internal support is the consumption of valuable time. Engineers frequently interrupted to provide support can find their workdays fragmented, making it challenging to concentrate on and complete their primary tasks.

- Impact on task estimation. Continuous interruptions from support duties can cause engineers to miscalculate the time required for their primary tasks. This can lead to missed deadlines or rushed work, affecting the quality of deliverables.

- Cognitive load. Fielding questions and troubleshooting for peers often requires context-switching, which can be mentally taxing. This constant shifting between tasks can lead to mental fatigue, reducing the engineer’s overall efficiency and capacity for problem-solving in their core tasks.

- Increased pressure. Engineers who possess specific expertise or knowledge might find themselves constantly approached for assistance. This can create an imbalance where certain team members are shouldering more than their fair share of the support load, leading to burnout. Over time, constant interruptions and an over-reliance on certain team members for support can lead to feelings of frustration. If not addressed, this can impact team morale and cohesion.

- Siloing and reduced learning opportunities. If a subset of engineers is always providing support, it may prevent others from developing problem-solving skills and self-sufficiency. Relying heavily on certain team members can stifle growth opportunities for the wider team. Similarly, if only a few individuals are leaned on for support continuously, it may lead to a scenario where critical knowledge resides with just a few team members. This creates vulnerability in the team dynamics if those individuals are unavailable.

External support

External support, especially for customers, users, and user-facing colleagues, comes with its own unique set of challenges. A primary hurdle is not just the unpredictable nature of the requests but also the broad spectrum in the quality of these requests. Some may be straightforward and easy to address, while others might be vague, complex, or even misdirected, requiring more time and effort to resolve.

To manage these sorts of demands, tools and processes like ticket queues and work-in-progress (WIP) limits are invaluable. Here’s why:

- Visibility. With ticket queues, there’s clarity. They provide a clear view of the incoming requests, shedding light on the current workload and the type of issues being raised.

- Prioritization. Understanding the queue helps in resource allocation. It becomes feasible to triage requests, ensuring that high-priority or urgent issues are addressed swiftly.

- Workload management. WIP limits act as a buffer, ensuring that support teams aren’t swamped with an unmanageable number of requests at once. This allows for a consistent quality of support.

To further streamline the process, “office hours” can be a boon. Setting specific periods dedicated to addressing external queries ensures:

- Predictability. Both the support team and those seeking support have a defined window. This clarity helps in setting expectations.

- Focus. When not in the office hours window, teams can redirect their attention to other pressing tasks, ensuring a balanced distribution of effort and time.

Additionally, proactive measures can be a game-changer. By equipping users and clients with resources, guides, or training sessions, many common issues can be preempted. This approach doesn’t just lead to fewer support requests; it also fosters a sense of empowerment among users, enabling them to troubleshoot or find solutions on their own. In the long run, it cultivates a more knowledgeable and self-reliant user base, leading to a more efficient support ecosystem.

Production incidents

Just as all meetings aren’t created equal, the same goes for incidents.

When assessing incidents, several factors matter. The frequency of these incidents speaks to how often they’re cropping up. Severity reveals the depth of the problem — is it a minor hiccup or a full-blown outage? Then there’s the impact, which dives into the broader consequences on both systems and users. And of course, the time spent encompasses not just the incident duration, but also recovery and subsequent investigation periods. If you’re tracking these parameters, do it transparently. Metrics should inform, not intimidate, ensuring no one feels the need to underreport or diminish the scale of an incident.

Not all incidents cast the same shadow. For instance, a brief slowdown in a non-essential service, though inconvenient, isn’t on par with a major security breach that jeopardizes user data. Similarly, a glitch experienced by a small subset of users during off-peak hours contrasts sharply with a system-wide outage at the height of business operations.

Post-incident reviews can be transformative, providing a platform to dissect what went wrong and how to prevent future occurrences. By identifying patterns and drawing up actionable items from each incident, teams are better poised to anticipate and mitigate future challenges.

Moreover, integrating tools for incident analysis can offer granular insights, highlighting potential areas of vulnerability. The implementation of a first-responder rotation ensures a dedicated team is always on standby, primed to tackle incidents, and distribute responsibility more evenly.

Ultimately, the aspiration isn’t to sculpt a world devoid of incidents. It’s to create a resilient environment where teams can swiftly recognize, adapt to, and learn from these interruptions, ensuring a consistent focus on the pivotal tasks propelling software engineering endeavors.

Are you operating in an interruption-aware environment?

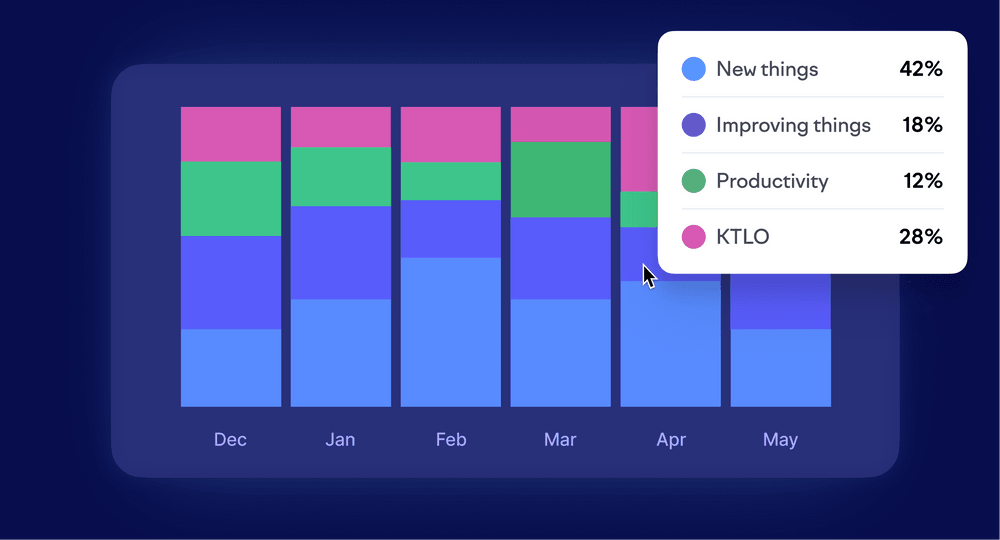

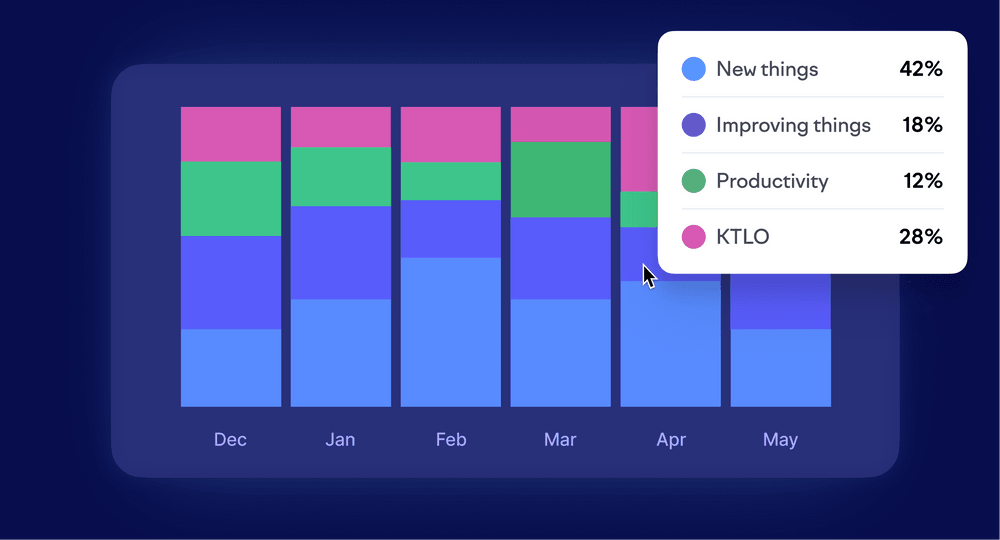

- Do we have a system for tracking and categorizing interruptions? Understanding the nature and urgency of interruptions can go a long wayto in managing them effectively. Are we capturing data on what kinds of interruptions are most frequent and what types disproportionately affect certain team members? This would help in deciding where to invest time in process improvements.

- Are we measuring the right metrics? Metrics offer a quantitative way to understand the burden of interruptions, but are we measuring the things that truly matter? For instance, beyond just tracking the number of meetings, are we looking at their ROI? And when it comes to internal and external support, do we have visibility into how much time is spent and the quality of those interactions?

- How elastic is our utilization rate? If we aim for 100% utilization, we’re setting ourselves up for failure. What level of buffer time do we build into our sprints or roadmaps to account for the inevitable interruptions? And are we revisiting these assumptions periodically to ensure they still hold true?

- Do we have a strategy for knowledge sharing? Many interruptions, especially internal support ones, can be reduced through better knowledge sharing. Do we have a centralized repository, internal forums, or other mechanisms where team members can find answers to common questions? How often is this resource updated, and is it easily accessible to everyone?

- Are we adapting as we scale? The dynamics of interruptions can change significantly as the company grows. Are the processes we’ve put in place scalable? For example, informal communication might work in a smaller setup, but as we expand, do we need to consider more structured channels to manage interruptions effectively?

Asking these questions can offer engineering leaders valuable insights into how well the company is prepared to manage interruptions. The goal isn’t to eliminate them entirely but to measure, reduce, and manage them in a way that aligns with the team’s needs and the organizational objectives.

By taking a nuanced and proactive approach to these interruptions, software engineering teams can build more sustainable, efficient, and harmonious work environments. When you make your processes interruption-aware, your team can focus on what they do best: building great products.

Subscribe to our newsletter

Get the latest product updates and #goodreads delivered to your inbox once a month.

More content from Swarmia