- Product

- Changelog

- Pricing

- Customers

- LearnBlogInsights for software leaders, managers, and engineersHelp center↗Find the answers you need to make the most out of SwarmiaPodcastCatch interviews with software leaders on Engineering UnblockedBenchmarksFind the biggest opportunities for improvementBook: BuildRead for free, or buy a physical copy or the Kindle version

- About us

- Careers

Structuring engineering organizations

Have you ever worked for a new startup with just a couple of developers? It’s pretty amazing, for a while.

You know everything about the business domain. You know the whole codebase because you mostly wrote it. There’s no decision you can’t make yourself. You’ve been spending time with the same two people, so you know how they think and how to best communicate with them.

It feels like the team is flying. New features are shipped to customers every week.

Fast-forward five years. Your company has been successful, but the complexity has grown significantly. There are product areas that no one on the current team has ever touched. The business domain has expanded in every direction imaginable, and there’s not a single person who can talk about all the details regarding every corner of the product. You’ve never met 80% of the employees. You wouldn’t know who to ask if you need help with an obscure technical question. You're spending more time getting buy-in from leadership for single features than actually building them.

It’s difficult to feel ownership of something supposedly owned by a hundred people.

Why do you need teams?

Teams split an overly complex domain into smaller pieces, allowing a group of people to feel a higher connection with their objectives, owned codebases, and their teammates.

To some degree, teams are silos. When you create a team, you’re saying it’s important for this group of people to be in sync with each other, but they don’t necessarily have to be quite as in sync with others. Silos are usually mentioned negatively, but without some intentional and well-designed siloing, people would get constantly overwhelmed and zone out with topics that they need to stay on top of.

Tradeoffs in organization design

Antipattern: Frontend team and backend team

A couple of years ago, it was common to split into a “frontend team” and a “backend team.” This way, backend developers would not need to be bothered with dirty details of the frontend, and vice versa. You would also get to work with people whose skillsets you understand.

This structure optimizes for learning about your craft (either frontend or backend), and collaboration within your team might feel easier.

Unfortunately, this setup fundamentally limits a team’s ownership of their area. Since practically all new functionality will involve changes in frontend and backend, teams cannot necessarily control their backlogs. Someone outside the team needs to manage the projects, asking teams to deliver tasks.

This arrangement also means that the software lifecycle is easy to ignore. If the team is just a puppet for someone else, who will take care of technical debt or proactively invest in some platform work? The team will likely ask for time for their priorities, and usually, those requests won’t be entertained.

Antipattern: Shared backlog

A similarly problematic approach is to have multiple teams working from a shared backlog as “feature teams.” It works for people prioritizing that shared backlog since they have more control over what gets done.

From the team’s standpoint, it has many of the same issues: the software lifecycle is forgotten, the team doesn’t have real ownership of the codebases, and they always have to learn new product areas when starting to work on a feature.

Maybe most importantly, every team has to deal with the full complexity. The team split fails to reduce the cognitive load experienced by the teams.

What’s most important?

Organization design is about dealing with tradeoffs. Since every communication path cannot be the strongest one, you have to choose what you prioritize over other things.

In most cases, you’re building software for a business, and there lies your answer: your ability to drive business outcomes is the No. 1 priority. Building software needs to be a good investment.

A team is most likely to drive business outcomes when it can make good decisions about its direction, iterate quickly, and is not slowed down by dependencies.

Teams are empowered to make these decisions when they have clear objectives and have a specific area to work within. Once those two pieces are in place, it’s less important to know the exact features in the roadmap. When the team learns something new, they can change the roadmap. The team can choose to invest in the technical architecture to move faster.

Organizational tradeoffs

Designing a software engineering organization is a multi-variable optimization problem where you try to balance the following considerations:

- Outcomes. What does the company want to invest in, and what business metrics are important to move? If you’re already investing in something, are you getting there quickly enough?

- Features. Every feature in your product needs a team to own it. It should be clear who will fix bugs or make small improvements in existing features based on the ownership.

- People. Besides a few cross-team roles like Staff Engineers, developers should have the luxury of being a part of a single team. You’ll need to build teams that include diverse viewpoints and skill sets.

- Architecture. Conway’s law shows the connection between organizations and the software architecture, and it’s one of the biggest limiting factors for scaling an organization. Designing a software organization requires a deep understanding of the software architecture.

These four parameters define the team’s boundary of ownership.

There is no simple algorithm for creating your teams — you’ll have to try different combinations to see how they might work. One approach to consider is a simple spreadsheet that contains all of these dimensions; you move cells between the teams to see how balanced the team would be. Sometimes, you’ll move a developer together with a feature they have worked on to make it easier for the receiving team to accept new responsibilities.

You’re going to evaluate a set of tradeoffs for each team, with things like:

- Do they have all the skillsets required for their objectives and codebases?

- How many dependencies on other teams are they likely to have?

- Is it close to an optimal team size?

- Is everyone getting the coaching and support they need?

- Have we standardized things where it makes sense?

- Does our software architecture support this team structure? (Reverse Conway’s law suggests that your software architecture limits the kind of organizations you can build.)

- How complex is the domain?

As a rule of thumb, these teams will be relatively full-stack, combining skills from different parts of the technology stack. You’ll likely also want to cover skills like design, data science, infrastructure, and product expertise.

Oftentimes, you’ll have to compromise. For example:

- It’s usually better to have one awkwardly big team than two teams that think they’re independent but depend on each other for everything.

- Having only one mobile developer in a product team might not be optimal, as getting their code reviewed and standardizing things with other mobile developers could be difficult. While it’s generally good practice to have all the skillsets in the product team, sometimes it’s not feasible.

- Instead of reporting to another frontend developer, frontend developers could belong to a club, guild, or chapter (you might even get away with calling it a posse). A more informal group could serve the purpose of building alignment and sharing learnings.

- Sometimes, the codebase is too tangled for multiple teams to share ownership. You might realize that in order to scale the team, you’ll have to invest in paying back some technical debt or extracting a microservice.

Reporting lines

Most commonly, all software engineers report to a team lead or an engineering manager who is familiar with their day-to-day work.

There are a few different alternatives for sharing the management responsibilities in a team:

- Your ability to manage projects from start to finish makes you a senior software engineer. This means that whoever is running the team hopefully doesn’t have to spend their time running the individual projects and can instead focus on the team.

- Some teams have a lead developer who’s not a people manager but who’s expected to ensure that the team practices are running smoothly and that none of the projects are stuck. They tend to be a developer who has been promoted to this role.

- Sometimes, teams have an engineering manager who focuses completely on that team. Their responsibilities include the lead developer’s responsibilities and the people management responsibilities of their team.

- You could also have a lead developer for each team, along with an engineering manager or an engineering director who looks after a couple of teams and takes care of the people management responsibilities. This is a way to bring some of the more senior management experience to the team, but it’s often more difficult to coach the team members from the outside.

These are tradeoffs you need to make based on the kind of management talent you have available.

Responsibilities like facilitating daily standups or team retrospectives can be rotated among team members. Having someone other than the team’s manager facilitate meetings levels the playing field for conversations.

Product managers and designers typically report to someone in the product organization, but they are usually placed in engineering teams and participate in their teams’ rituals. This helps them build consistency for the product across different teams, and these roles have an inherently high amount of collaboration.

Types of teams

Team Topologies introduces stream-aligned teams, enabling teams, complex subsystem teams, and platform teams.

I like simplifying the model a bit: product teams are the vertical slices of your organization, and platform teams are the horizontal slices. Their communication patterns are quite well-established. Sometimes, you will need special teams where you need to design their roles case-by-case.

Start with product teams

Most of your teams will be product teams, as defined in Empowered by Marty Cagan. It’s similar to stream-aligned teams in Team Topologies. They will own a slice of your business domain and can make decisions and deliver features independently with minimal dependencies.

These teams will allow you to split a complex domain between multiple teams, and they will maximize the speed of delivering business outcomes.

A big part of your organization’s growth will simply involve deciding where to invest more and carving out responsibilities for a new team in that domain.

Example 1: Food delivery

For an imaginary food delivery business, you might start the organization design by considering the three core audiences it serves: consumers, restaurants, and couriers.

Each team has a different persona they listen to and whose problems they’re trying to solve. Prioritizing becomes easier when they know where to source their feedback.

In practice, each persona also uses a different software product. Restaurants manage their menus from one application, couriers navigate to their destination with another, and consumers order food from a third application.

In the background, the software architecture supports scaling as well. The service that routes couriers to their destination is decoupled from the rest of the business.

Each one of these teams can be split into smaller teams. Once you’re growing the organization enough (because, presumably, you’re trying to move very quickly), you’ll discover that each team owns a relatively small part of the puzzle.

At that point, some of the previous tradeoffs might tip over — for example, it’s perfectly normal to have technology-specific teams working on a single, very valuable codebase. Team Topologies have the concept of “Complex subsystem teams,” which could be a microservice with many scalability needs.

Example 2: B2B SaaS for developer productivity

Our organization at Swarmia is built to deliver a B2B SaaS product to help software development teams in the engineering effectiveness space.

For our business, we’ve identified the following important guiding principles:

- Our customers need to be able to trust the data from GitHub, Jira, and other tools — even when teams use them differently or when Jira hygiene is not perfect.

- We must provide value for everyone in the organization — from CTOs to software engineers. Their use cases tend to be quite different.

- Rather than rapidly increasing our headcount, we want to automate our work and help our customers solve their problems independently.

The business and what’s unique about us sets the frame for organization design. This led to us assigning the following outcomes, features, people, and architecture elements:

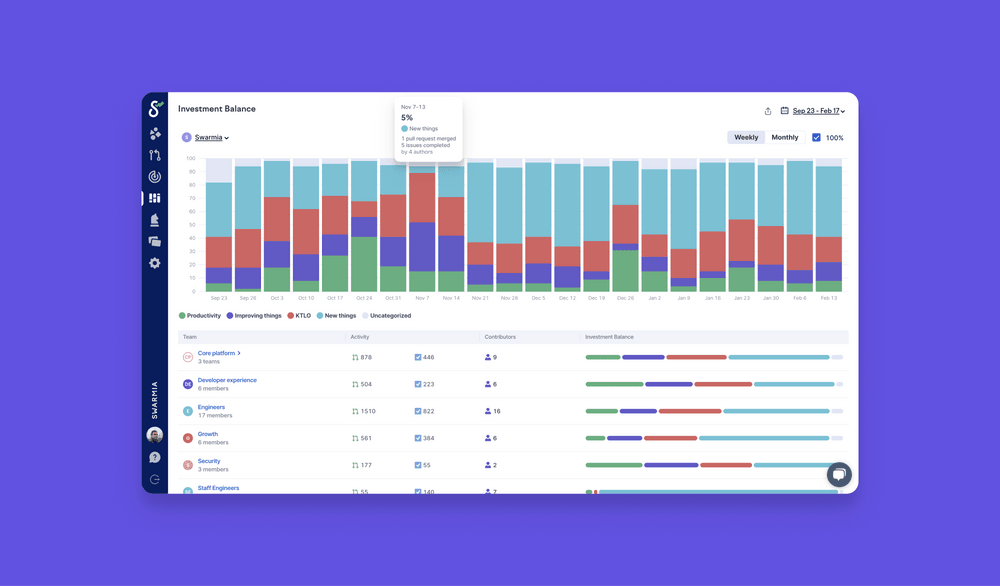

Team: Core (Dumbo)

- Outcomes: Engineering leadership and managers know where they should focus their attention

- Features:

- Organization-wide insights

- Investment Balance

- Software capitalization reporting

- People: Full-stack developers with data visualization skills

- Architecture: Building features on top of the data platform

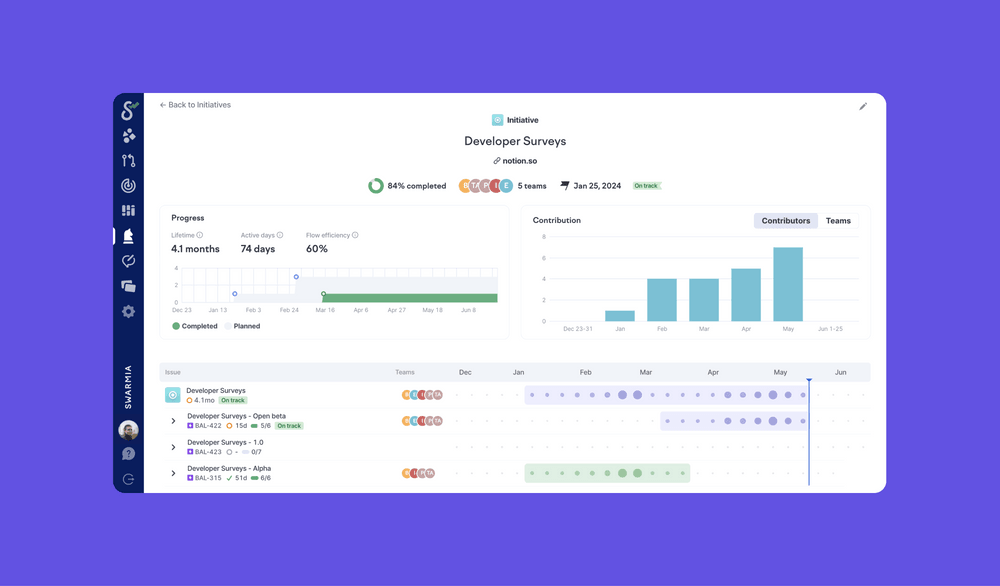

Team: Developers (Ballmer)

- Outcomes: Individual contributors and teams run continuous improvement on autopilot — from identifying problems to doing something about them

- Features:

- Developer Surveys

- Developer Overview

- Deployment Insights

- CI/CD Insights

- Working Agreements

- Slack integration

- People: Full-stack developers who are motivated by building developer tooling

- Architecture: Building features on top of the data platform

Team: Growth (Groot)

- Outcomes: Driving organizational efficiency with our self-service product, customer onboarding journey, and internal tooling

- Features:

- Marketing website

- BI data warehouse, integrations and reporting

- Internal admin dashboard

- Product onboarding

- Subscription management

- People: A Team Lead who actively also works with marketing; data pipeline expertise; full-stack developers

- Architecture:

- Separate data warehouse (BigQuery) and data pipelines (Dataform)

- Integrations with off-the-shelf tools (Fivetran, Rudderstack)

- Separate admin panel

- Separate marketing website

- Often builds on top of codebases owned by other teams

Team: Platform (Yoshi)

- Outcomes: Making it easy for other teams to build scalable features with reliable data integrations

- Features: Data integrations (GitHub, Jira, Linear), data querying framework

- People: Full-stack developers with strong database fundamentals and more DevOps experience

- Architecture: Owns a big PostgreSQL setup and the Kubernetes cluster

Unsurprisingly, this structure affects how we build software too.

Find leverage with platform teams

Once you have a few product teams, you will discover that they sometimes act like independent companies. This is by design, but some standardization would benefit the teams.

No matter how important an objective is for your company, you can’t suddenly assign a thousand engineers to work on it and expect results. This is why Big Tech often has 50%+ of their engineers in platform teams with the objective of making the rest of the engineers move faster.

The idea with platforms is that you should get really good at whatever your company is doing a lot of. Sometimes, it’s the more obvious answers, like deploying code to production — yes, you should have a CI/CD pipeline. These platforms could also come in the form of:

- Design systems that make it easier for all frontend developers to build consistent UIs

- Scaffolding to deploy new microservices quickly in the company’s cloud environment with all the security & compliance requirements checked and with a good developer experience

- Tooling and libraries to visualize data in a data-heavy product

- Ways to build integrations for an integration-heavy product, with tools like debugging webhooks and building authentication flows

- Ways to tackle the app performance issues so that teams can build features without worrying about scalability (quite as much)

- Abstracting out any other nasty detail of your business so that everyone can move faster

Thus, platforms give leverage to teams and help your organization move faster.

Special teams

As the organization continues to scale, certain areas that don’t fit neatly into existing product or platform team structures will emerge. In these cases, you may have to get creative and design another type of team.

Product and platform teams have fairly simple patterns of ownership and communication needs. At some point, you’ll want to make a tradeoff that doesn’t perfectly fit these models, and that’s fine — as long as you recognize the tradeoff you’re making.

This could be teams like:

- Enabling. They could be helping the rest of your organization with security, recruiting, onboarding, or any other crucial aspect.

- Complex subsystem. Sometimes, a system is important enough to warrant continuous investment in a team that maintains it.

- Temporary or project-based. These teams are often formed to address specific challenges or objectives and may be disbanded or reformed as goals are achieved or priorities change. This could be a big migration from yesterday’s testing framework to whatever we do today. Be aware that they might leave behind code whose ownership is questionable.

- Objective-driven. Some teams are defined by specific objectives they aim to achieve, not by a product or codebase boundary. This could be a team that’s focused on cross-cutting customer onboarding experience. A significant portion of the team’s work involves collaborating in areas owned by other teams. This requires them to have strong cross-functional communication and coordination skills.

Your organization might not need these types of teams right now, but having it in your vocabulary can be helpful when a team is venturing into this direction and feels frustrated by the collaboration overhead. There’s no escaping this type of work, yet it can be very impactful for the business.

Teams as an investment

Congratulations, you have mapped out the organization you currently want to build. Now what?

As an engineering leader, you have a couple of responsibilities that no one else in the organization is likely to do for you:

- Communicate engineering & product priorities and progress with your Board of Directors and the rest of the company.

- Figure out the hiring plan, sell it internally, and decide where to invest the headcount.

- Stay on top of the priorities, the architectural issues, and the target architecture.

- Make sure that teams’ objectives are aligned but not too overlapping.

- Help teams where they’re struggling.

Traditionally, product investments were made far from the engineering teams. The company would decide to fund “projects” and “features,” often without much detail about the implementation options or the competing priorities — and often with no idea whether the customers really needed it.

With empowered product teams, your main unit of investment is a team. You fund a team to work on an objective, and they’ll prioritize features and other types of work to get there. If you want to move faster towards a goal, you can sometimes choose to invest in more than one team — but you might need to pace your investment over a longer period.

Some companies take self-organization too far, treating goal-setting as a team-only activity. While it’s a good idea for the team to drive the goal-setting process, as an engineering leader, you can support the team in choosing the right objectives. You’ll have more context from all the other teams and must ensure the team objectives collectively map to your strategy.

As a leader, you’ll want to track your company objectives and all the projects that are contributing to them. Ideally, the company objectives are in priority order (or there’s just one of them!) so that each team knows where their help is most needed. You can follow whether the teams are constantly getting work done in their areas, or if they got dragged to something else.

These other priorities are sometimes easier to see from a team’s investment balance. The Balance Framework helps you understand how much each team is spending on keeping the lights on, building new things, improving existing features, or improving productivity.

For example, a team that’s spending 80% of their time just keeping the lights on can’t complete many new product features.

Dependencies

One of the main goals of your organization structure is to minimize dependencies. Product teams own domains and components in their area, and platform teams serve other teams through clearly defined application interfaces.

Unfortunately, if your team truly pursues its objectives rather than trying to stay in its lane, eventually, it will need to do something that depends on another team.

Dependencies are the problem that will break your plans. A project might only have two weeks of work, but it could take 6 months of calendar time if you need to convince other teams to change their priorities.

Historically, companies have attempted rituals like “Scrum of Scrums” to coordinate between the teams. Some organizations align sprint start dates between the teams to get them “marching” in unison. The real issues are rarely uncovered in a “Scrum of Scrums” meeting because updates are shared at a high level, and the real problems are in the details.

The main strategies for dealing with dependencies are:

- Avoid dependencies. Is your organization structure right?

- Create a self-service platform. If a dependency is very common, the team can build APIs that make it easier for other teams to build functionality on top of it.

- Establish rules for working on someone else’s codebase. The team that needs a feature should be able to create a pull request in another team’s codebase while getting a review from them. You might want to plan the change together.

- Be clear about company priorities. When another team is working on a company priority, other teams are expected to accommodate their requests. You can’t have too many priorities for this to work.

- Loan a developer from another team. Get a specific person to help with the problem domain and codebase, and make this arrangement explicit for a few months. They will return to their home team with domain knowledge from the other team.

- Hire a technical program manager to collaborate with multiple product managers in other teams. Project management can be a full-time job.

You do you

Hopefully, these guidelines will help you recognize what to consider when building a software engineering organization.

Ultimately, it’s always a tradeoff, and the real world is full of nasty details (so you have one designer for the 100 developers?).

Consider sharing this blog post with your engineers so that they know how you think about building the organization because many of the details will come from your developers directly.

Subscribe to our newsletter

Get the latest product updates and #goodreads delivered to your inbox once a month.

More content from Swarmia